“…..because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know…..”

Donald Rumsfeld

Aided and abetted by corrupt analysts, patients who have nothing better to do with their lives often use the psychoanalytic situation to transform insignificant childhood hurts into private shrines at which they worship unceasingly the enormity of offences committed against them. The solution is immensely flattering to the patients, as are all forms of unmerited self-aggrandizement; it is immensely profitable for the analysts, as are all forms pandering to peoples vanity; and it is often immensely unpleasant for nearly everyone else in the patient’s life

Thomas Szasz

“You will always be fond of me. I represent to you all the sins you never had the courage to commit.”

Dorian Gray (Oscar Wilde)

Though both can be, so to speak, a gazing up and into our rear ends, psychotherapy, unlike colonoscopy, is a word without denotation. It may once have had a chance of indicating an asymmetrical relationship between two persons where one takes the role of navigator or interpreter of the inner world and life of another to arrive at a place of understanding of who the patient is and how they arrived at the current state of being. An impossible task from the outset. Just as mental health is subsumed within a model of the mind in its abstractions which lacks an answer (see chapter on epistemology of mind), the explanation of who I am and the journey I have taken must necessarily be subsumed within an ever-expanding realm of social, political, metaphysical and a/theological life. The larger picture really does matter towards the goal of the well examined life. Meanwhile we more mortals vainly (or valiantly?) stumble and tumble over speculations held at best as articles of faith so as to launder the want for understanding into what is taken to be discovering oneself.

Needless to say though say it I shall, any thoughtful person must surely acknowledge that the subjectivity and other limitations of the therapist are insoluble obstacles to the confrontation of the patient with their objective selves, to say nothing of the patient’s limitations in being their own guide. Even two coming together on a Kabbalistic journey (is that what psychoanalysis was born of?) are limited by their own schemata. If such a thing as the objective self exists, surely the only psychotherapist worth their salt is the divine and the only one who can ever know themselves is the same. And so either in our ignorance or to defend against the despair of interminable unknowing we collapse the tension of an unrequited will to truth into the contentment of embracing idols of our own making. That is most of the psychotherapies in a nutshell. A number of small “c” cults with upper case acronyms.

Unfortunately, those deep torturing doubts that are my constant companion never seem to trouble the mind of the proverbial ninety-nine point nine recurring percent of psychotherapists, and scarcely ever does it pass through their minds if they really can know anything about the person so as to give license to having discovered what they have claim to have found in the depths of their psyche.

These sandy headed ostriches can be sympathized with as victims of their own defence mechanisms, and I am a victim of my own analysis of them (see how it works). But narcissistic defences to know what cannot be known are not a get out of jail cards for inventing fantastic and sometimes depraved models of the psyche and schools of psychotherapy. The behaviourist school, in its more radical excursions, was taken to deny if not the value of exploring the mental (a cowardly defence against not knowing), to denying the existence of the mental altogether (an absurdity). This absurdity is approached in the third chapter on mind. And contra the behaviourist school may be various readings of the first analyst Freud was not the first to suggest that mind and behaviour, though ultimately materialistic, is operationally governed by the cognitive and emotional subsurface known as the “unconscious”. Thus analysis too was a retreat of a kind from the givenness of mind as we experientially know it to a different kind of negation. And whereas the behaviourists denied what cannot be denied (i.e. mind), the analysts and their heirs invented what cannot be falsified. Both in their way became cults.

Between the two there are innumerable schools, each to varying degrees kissing cousins or the chalk to the others cheese. Each may be said to lay claim to the model of the psyche, and thus the model of psychological suffering, and thus the model of recovery to whatever we should be (are you sniffing religion yet?). Ironically the closer they are the fiercer may be the battles between the cults to claim the knowledge of the person, knowledge I have concluded is a priori impossible. There are the pure Lacanian Freudians, object relationist Kleinians, so called middle school, Jungians (pre and post having been influenced by his narcissistic pseudo-psychotic pagan occult phase right on up to the confused neo con Jorden Peterson), humanists and so called existential psychotherapists, family systems and cyberneticists, cognitive behaviourists, gurus of many mindfulness approaches, fusion and eclectic psychotherapists, attachment theory universalists, face tappers and so on and so forth. The numbers of the various psychotherapeutic schools can be as great or as few as one wishes. Insomuch as they are, after all, nominally different schools, they number at least a hundred. Insomuch as divisions may be (mis)placed, some may schematically number them in as few as four main groups (e.g. cognitive behavioural, humanistic, mindfulness and analytical). This too is problematic. For example, the cognitive behavioural school, narcissistically considered the “scientist practitioner model” and erroneously linked to Socrates and the stoics, is fundamentally deeply analytical in it being predicated on discovering the gnostic “core belief”. Pray tell how deep does the core go? What is its origin? What is its architecture or topography? Is not the discovery of the core belief a telling to the therapist what they wanted to hear, and what the therapist hinted at finding all along? And from what source come the drives towards these contrivances? Aaron Beck himself arrived at his CBT through an analytical approach (including dreams) and a reasoning necessarily contaminated by his Freudian past, and he left his creation to a daughter heir, just as Freud did with his and Peterson the Jungian will do with his. Insomuch as some might be inclined to heap negative criticism on psychoanalysis, if the trunk is rotten, are not the branches also? And let it not be lost on us that all the mindfulness schools are, to be frank, dissimulations, plagiarisms and permutations of various of the more contemplative schools of religion, leaving behind what those religions would say is the most important aspects to grasp and practice.

Some would say of all of this that none of it matters. They would say that the key feature of any good psychotherapy is the so called “common factors”. That is to say, whether the patient sits across from a Freudian exploring their Oedipus complex or the existentialist exploring their anxiety as borne from fear of personal meaninglessness and mortality, each will languish or triumph on the basis of variables such as regularity of appointments, mutual commitment, mutual trust, unconditional acceptance and the therapist’s caring intentionality directed towards the patient (a kind of love).

And that dear reader, leads us to the greatest rot up from the roots of the tree of the psychotherapies. All the above fluffy caring common factors sounds like delectable fruit for sure. Yet this is a distraction from the corrosive implications. For starters, a therapy that can be anything (providing it contains the common factors), is indeed a therapy of nothing at all. Certainly, all therapists in one fell swoop lose the status as authority figures, that is unless they cunningly attempt to reify the common factors as a special technique of an expert intelligentsia. Indeed, some do just this, kicking up a fuss about the therapeutic frame of regularity of time, place, even location of the chairs in the therapist’s rooms. But this political power play won’t fly. One can just as well achieve the common factors in a caring conversation with a friend at a cafe, or with ones caring grandmother or pastor or spouse. Even a stranger at a bus stop may do as one off therapy, providing love pierce through the alienation. And therein also lay a sinister implication of the role of therapists as proxies for what ought to be already in place in the community. Each therapist ought to feel a sense of dread for they are a living and sad indictment on the state of the world that outsources what ought to be insourced. Why are they even needed? We are the pathos of the world as much as the patient, a sign that the community either does not care or has divested itself of common or good sense. Moreover, in virtue of being there to be used, they are an impediment to the community qua community being forced to confront its deficiencies and find the remedy within itself. To wit, perhaps the best psychotherapy is the one that simply ceases to meet with patients and allows itself to die into the pages of history. For only in that death can a community confront what requires confrontation, complete its own psychotherapy, and finally grow up.

Secondly, if it is true that the common factors are the force towards recovery and not the specific theoretical schemata this creates a short to midterm problem. What would a therapist say, if to tell a patient that their specific therapeutic modality is just a play with metaphor and the frame is the real canvas? Could they say that their interpretation of the patient on modality specific lines is “just a” convenient story towards an end? Would it not lose its placebo power, the mystery lost like a shaman who reveals that the dance is just a dance, the talisman is just wood or stone? The commitment to therapy itself would then be a suspension of the will to truth, a commitment to pragmatism. And this, as I argued in a previous chapter is morally fraught.

And finally, for now, discussion of the relative truth value of the therapies versus one another versus the notion of the common factors, all this serves as a diabolical red herring. Which therapy is more effective than the other is also a fraught question. We can pursue this debate throughout the twenty first century as we did in the last, I would predict with surety against any prospect of resolution. Yet the question of theory is not then resolved by shifting to which therapy “works”. The question is what is it for therapy to work? What is “recovery”? What ought recovery be. How would we know? Where are the boundaries between symptom alleviation as morally neutral and morally charged? Surely these are the questions that ought to be resolved in the mind of every budding therapist before sitting across from a patient. These concerns are borne out in a thought experiment. Let us imagine the patient is a serial rapist. And let us imagine that he has convinced us as to the error of his former ways, and that he is a changed man. So changed in fact that he is plagued by the pain of conscience. This is not pain of unwanted temptation of his previous drives. He is cured of temptation. The pain has no utility and he shall rape no more. No the pain is instead a painful manifestation of memory pure and simple. Needless to say it’s a challenge to ego strengths and that greater evil known as “self esteem”. Now our ex rapist wishes to forge and convinced us that that memories of the past are not necessary in order be safe to others in the future. Let us imagine you are the therapist, a hypnotherapist of renown. You have the power to make him forget. You have the power to relieve him of his symptoms and effect what could be considered a recovery and “make him happy”. So what do you do and why do you do it? Your answer to this question, and indeed every psychotherapeutic encounter at least to some degree, is a necessary encounter with morality. What is the value of memory? What is the value of anxiety? What is the value of pain and not being happy? What is the good life, the well examined life, and how are those with whom I have lived to be remembered? What part did I play in where I am? What is it best to be and become? To such a hypothetical patient as our rapist you may refuse to offer your services and have your own moral reasons. Or you may accept, again with moral justification. Or you may accept simply defining yourself as a mercenary against memory, alleviating symptoms and going where the money takes you, where the patients’ values are your values for the prostituted hour (after all judgment is a crime). To wit you are in the land of a morality whether you like it or not, and in any direction you turn questions may be rightly raised against you, perhaps more than your “client”. Are you comfortable being a mercenary or prostitute (pick your analogy)? You see pragmatism is a many headed Hydra. And it rears its ugly heads again and again and again in every school of psychotherapy. But arguably no head is more grotesque and mystifying than that known as Intensive Short Term Dynamic Psychotherapy, or ISTDP. It is the worst symptom of the disease that is psychotherapy and ought signal us to examine the roots.

What is ISTDP about?

For this chapter I draw primarily upon two introductory articles in the American Journal of Psychotherapy, Vol. 69, No. 4, 2015 by Catherine Hickey, M.D, along with another by the same author in Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 43(4) 601–622, 2015, and finally the published journal articles by Allan Abbass and texts of ISTDP circa the same years and before. All are faithful to the metapsychology and practice of ISTDP at the time of my own writings.

ISTDP’s unstated predicates are simple enough and shared with many other schools of psychotherapeutic thought and practice. Just three of these will be mentioned for the benefit of the lay reader. Imagine all the machinations of your conscious mind. What this mind might be was discussed in chapter 3, yet includes all the interior world your awareness, i.e. the stream of conscious thoughts infused with emotions as the collective modus operandi behind your deliberate behaviours as observed by others. Or all this would be the modus operandi were there not the alleged unconscious, the real master of who you think you are. The content is different down there in unconsciousland, often symbolic in its representation and the conflict often more dramatic. Yet its conceptual geometry is thought to be much the same form. Your surface mind has interior mental action. It thinks about things. It feels about things. Sometimes it thinks and feels too much or in unhealthy ways. It plans and deliberates. And so does your unconscious. The only difference is that one is largely contingent and you are aware of (conscious) and the other is largely determinant and something about which you are unaware (unconscious). The machinations of the latter are purported to reveal itself only in tantalizing lifts of the veil such as in dreams or slips of the tongue (Freud) or in something as benign and indirect as a sigh or becoming distracted when certain themes are being discussed (ISTDP).

Consequently, Freud may say that your surface fears of failure and anxiety, your frustrations and poor assertiveness stems from, in the cliché oedipal example, the unconsciously held desire for sexual union with your mother and the fear of being castrated, if not killed, by your father’s wrath were his unconscious to become ascendant. This is a conflict hidden from the conscious mind since childhood when it first became manifest to the unconscious, hidden on account of it being too threatening. (Melanie Klein of the so-called object relations school was even more radical in believing unconscious dramas to begin in utero, where every foetus is a little dramatist floating in its own stage of collective unconscious and narrative. The collective unconscious in turn partly began as a pagan occultist construct, partly informed by the proto fascist formulations attempting to account for degeneration of the inferiors of society and partly perhaps the doctrine of original sin etc). It is this fear within powerlessness that may explain why you are not all that you could be as an adult, and your trepidation to take the leap to make all your contemporary dreams come true. Or it is perhaps this fear why you were anxious to follow in the footsteps of your father, for to become the father can sometimes be the closest thing to victory over the same (if you can’t beat them, join them, if you can’t join them, become them), bit sometimes it can be a sign they have defeated you. Whether you are especially anxious to become your father or especially anxious to run in the opposite direction, both can be interpreted to mean the same thing, a convenient plasticity of interpretation which ought to raise suspicions in any critical thinker. Where Freud might have made libido (contra popular interpretation not entirely synonymous with lust) the primary driving force of the unconscious, other psychodynamic theorists are more brazen dissimulators of Nietzsche and the Teutonic soul than Freud was, in seeing power and domination the primary drive. Racialist esoterica would say this in turn reflects differences in the blood of the soul.

Others, more from softer sentiment and equally borrowing on wishful thinking than any evidence, conceive of love to be what makes the unconscious go round. But not ISTDP. As we shall see later, love is not what at all what they are about.

The second predicate, as exampled above, is that the unconscious conflict creates conscious (i.e. surface) neurosis, neurosis being an eloquent and now outdated term of art for a mixed bag of painful thoughts and feelings, potentially leading to maladaptive behaviour and general misery. To the extent none of us may lay claim to be Christ or a Bodhisattva, all of us to a greater or lesser extent are touched by unconscious conflict. The proportion naturally approaches one hundred percent of those seeking help by the psychiatrist. After all, why else are they there?

The third predicate is a practical one, that being that the way to rectify the conscious neurosis is via a raising the unconscious to the surface. Freuds authority afforded him a genteel approach. He essentially informed the patient of her unconscious machinations. Like Moses come down from the mountain, the information alone was proffered as sufficient to convey truth and effect recovery. For some reason it was lost on Freud and his heirs that when Sophocles tragic hero Oedipus acquired his own insight, that this was just the beginning, not the end, of his woe.

Intensive short term dynamic psychotherapy is further predicated on the following.

Firstly, ISTDP supposes that surface neurosis is caused by, and holding back from, the release of powerful emotions. Overwhelmingly in ISTDP literature the emotion in question is rage, pure primitive murderous rage directed at significant others from the past or present. Often the rage is sexualized, and by extension therefore often necessarily incestuous in that the significant figures of childhood angst is the family. It is murderous rage that makes the unconscious world go round.

Secondly, ISTDP relies upon an assumption that may be considered an unstated metaphor from either physical chemistry (almost an unstated application and perversion of Boyles law), or on the other hand a metaphor from economics. The idea is this; the patient’s unconscious will be resistant to releasing the painful shameful murderous rage. And so if the therapist applies extra “pressure”, the number of required sessions can be made fewer. They don’t quantify how the proportionality is scaled, yet it would not be a mischaracterization to say that if the therapist doubles the pressure the sessions ought to be (at least) halved to maximize therapeutic efficiency and bring the patient sooner to a point of recovery (whatever recovery is). The logic seems sound enough. Yet this mathematics is very strange in the world of human relations and psychology. Can we get to marriage with half the dinner dates, providing they are full of passion?

A glimpse into an ISTDP session or two

ISTDP is structured similar to other talk therapies. The patient sits in one comfortable chair and the therapist in the other, each chair facing or oblique to one another, each close enough, yet not too close. The ISTDP session will be videorecorded. This is exceedingly important (more on this anon). The therapist will ask questions about symptoms, about relationships past and present, the basic pedestrian stuff of any explorative psychotherapy. When supposedly painful and important material begins to emerge, the patient will “resist”, where resistance might be a sigh, a drifting off or distractibility as an unconscious tool of avoidance. Never mind the reader’s intuition that sometimes, as in the leitmotif to Casablanca, “…a kiss is just a kiss, a sigh is just a sigh….”. No, a sigh is always more than a sigh. And never mind that not all distractibility is dissociative, and how the therapist, that great gnostic exploring the inner world might possibly objectively discern the difference. Another psychiatrist might say the patient has ADHD. I might say the patient is just distracted per se, bored (perhaps with me) or has smoked too much cannabis today to maintain attention. In any case, our ISTDP therapist knows better. Resistance can also be manifest in muscle tensions, fist clenching, a tight throat and the like. At the right time the therapist will probe deeper as to the themes arising during these bodily revelations, eventually bravely meeting resistance head on, exploring feelings without retreat. ISTDP even has a technical term of art for this dramatic moment, the “head on collision”. Hickey also writes as to the attitude the therapist must take towards the enemy resistance

“the therapist must also convey a considerable amount of disrespect for the patient’s resistance”

The challenge to the resistance must not be prematurely applied however, as this will result in a failure to “unlock” the unconscious. I’ll refrain from what the Freudian what make from such a description of technique. Suffice to say a therapist wishing to satisfy their patient ought not to suffer from premature investigation.

The whole dance of the therapist asking questions, encountering resistance, pulling back and sometimes increasing pressure is known as the “central dynamic sequence” or CDS and has the following stages; inquiry, pressure, challenge, transference resistance, direct access to the unconscious, systematic analysis of the transference, and dynamic exploration into the unconscious.

Sounds like sophisticated stuff indeed, for what is essentially an exercise in psychological “button pushing” on one hand and Ellulian psycho-technocracy on the other.

The buttons being pushed are naturally seen within the patient from the beginning, though ISTDP has a remarkable talent for publishing cases in which the transcript clearly described what we in the trade call “leading questions”, that is to say a case of the therapist creating the button and then pushing it by stating “these are the facts of the ugly truth, don’t you think?” The outcome of the button pushing is what is also known in psychotherapeutic circles as an abreaction leading to catharsis, and what the laity might describe as losing one’s temper, having a cry and feeling much better afterwards, though hopefully a little guilty and embarrassed. The ISTDP community does not use the archaic terminology of abreaction and catharsis. To do so would diminish their claim to novelty and discovery.

What is distinctive about ISTDP, and I’ll grant it to be internally coherent to its theory, is that it’s abreaction of primitive murderous rage is itself full of murderous rage. This is manifest in what I can only describe as a therapist guided patient generated pseudo-dissociative role play of fantasy ultra-violence. That’s a mouthful and I shan’t dignify it with an acronym. Essentially what I am saying is that the patient is responsible for being coached to whip themselves into a frenzy to imagine themselves as brutally killing another human being who is the scapegoat for their neurosis, and even coached in how to kill them. Below is an excerpt from the transcript of a therapy session in Hickey’s first paper between a patient “PT” (of whom it is implied is actually a medical doctor in ISTDP training herself, as she is a professional therapist with a knowledge of surgical terminology) and “HD”, the discoverer and doyen of ISTDP himself, Habib Davanloo.

“HD: How do you experience this rage?

PT: I have a knife—I start attacking.

HD: But that doesn’t show how the rage goes.

(At this point, the patient has the full activation and experience of the

neurobiological pathway of murderous rage: She physically gestures as

though she has a knife in her hand and is slashing the therapist.)

HD: Don’t close your eyes. Don’t move too much. That’s not how you

hold a knife.

PT: Down and down (repeatedly).

HD: Go on. Go on. Let’s see how systematically you go. Go on. Go on.

Go on. (Here the patient has a massive passage of guilt. She is extremely

tearful.)

HD: Look to my eyes.

PT: I see my grandmother and mother together.

HD: Could you describe my eyes?

PT: They are green/blue. Why did I do this to her? Why? How could

I do this?

HD: Look to my murdered body. You said my eyes were

green . . . face with the feeling. Face with your feeling.

PT: I love you. I love you so much.

HD: You are talking to whom?

PT: My grandmother

HD: How does she look at you?

PT: She loves me too. I love you.

HD: How badly the body is damaged?

PT: There’s blood. I have carved. There is a big incision down her

head and down her neck and her abdomen is filled with blood. I’m so

sorry. I’m so sorry. I love you.

HD: Obviously you are loaded with the primitive murderous rage.

Look, you have to face the truth of your unconscious. You say you love

her but at the same time you have murderous feelings. You see the two

sides? A part of you wants to destroy her but another part of you loves

her. But you have to face the two sides of the ugly truth of your

unconscious. You have to face it.

PT: I have to face it.

HD: One part of you wants to torture her even worse than this.

Another part wants to love her. This is the ugly truth of your unconscious.

If you want to examine it we can examine it.

PT: I want to.

HD: There is a massive primitiveness, and it is extremely important

you examine . . . this.

PT: Yes, there is.

HD: You carefully want to examine it? If you want to put an end to it,

and I put emphasis on if, if you want to put an end to the suffering . . . .”

In a subsequent session the abreaction is even more graphic in its violence

“HD: How do you feel that anger towards me?

PT: I would punch you in the face with a knife—go right in to your

eyeball, slash down your eye, down your face, and down your chest

and abdomen. I would take a knife and put it up your rectum until it

comes out of your abdomen—it is a curved knife. I slice down and

mutilate you. I tear open with massive claws your abdomen—down to

your backbone, and there is a river of blood coming out.

HD: And then what is my situation? If you look at me I am disastrously

mutilated.

PT: (Appears to have massive waves of guilt-laden feeling). I’m sorry.”

ISTDP; How did it evolve?

ISTDP literature waxes lyrically and sycophantically about its founder and pioneer into the unconscious Habib Davanloo. The story goes that Davanloo started out in the 1960’s as a Boston psychoanalytic trainee of Elizabeth Zetzel, Eric Lindemann and Helen Deutsch. Davanloo was driven to discover why some patients recovered and some did not. Fortunately, over time and with advances in technology he was able to amass a huge library of filmed therapy sessions. Having settled into Montreal, Davanloo poured himself over the video footage to observe what occurred during those sessions that were allegedly successful, what was said and not said to “unlock the unconscious”. From this came hypothesis testing based on what was observed, resulting in new video-recordings of new patients, new viewings of video-recordings and ever greater refinements of technique with ever greater elaborations of the “discoveries” made as the fruits of “research”. Davanloo was said to accomplish what Freud never could, i.e. reliable recovery in a timely manner and with avoidance of the dreaded “analysis interminable”, i.e. psychoanalysis that goes on forever without any satisfactory therapeutic end point. The apogee of his “discoveries” was a metapsychology bloated with terminology and many an acronym (e.g. MUSC or multidimensional unconscious structural changes and the aforementioned central dynamic sequence or CDS), spiralling into elaborations only surpassed by other masters of fictional omphaloskepsis such as Ken Wilber and Carl Jung. The distillation of Davanloo’s metapsychology was not so great a departure to Freud in the inner conflict being partially guilt-ridden masochism (what Freud would call superego) fused with primitive murderous rage (clearly a variant on his id construct). That’s where the similarity ends.

The video-recording persisted and transitioned to become a necessary motif for ISTDP to this day, and held up as a necessary presence in every therapy session. Nowadays pilgrims flock to Montreal and other training Mecca’s to be trained in the art of ISTDP and unlocking the unconscious to fantasy murder and mayhem in intensive immersive and expensive workshops. As Hickey notes, trainee therapists are very often participants in recorded sessions themselves, both as fledgling therapists and patients.

ISTDP; A critique.

Does the unconscious exist, and how is it structured?

When I was a junior doctor in psychiatric training, we were at one point asked about our opinions on psychodynamic psychotherapy in general, and Freud’s psychoanalysis in particular. As it turns out I did take issue with the lot of it. “Well you wouldn’t deny the existence of the unconscious, would you?” came the reply from our instructor, as if to imply that from a belief in the Mediterranean Sea must follow a belief in Atlantis and her treasures submerged beneath it. What followed after some debate was some concession to the science as having moved on since Freud, though how such a “science” might have advanced when the unconscious in all its alleged forms is non falsifiable is beyond me, and only “science” in the most expansive and classical use of the term could have moved on. What he meant to say was psychiatric fashion has moved on driven by pharma. Psychodynamic psychotherapy is a science in the sense that almost anything can be argued to be a science. In what way does the use of a word (i.e. science) entail legitimacy?

Now much older, I’m neither about to deny the existence of the Mediterranean or the complexity of the person from which we might grope for metaphor of what lay beneath the metaphorical surface. But that is hardly a salve for my own ignorance, and I shan’t fill a vacuum with a lie.

Dreams, qua an alleged window into the unconscious, can mean anything and nothing and only have value as tools to explore what might be consciously held opinions and conflict. Some esoteric practitioners use tarot cards to accomplish the same, not as divinations to the future as opposed to themes to be explored. Disclosures during hypnosis are as good as worthless. Now I’m not about to commit the sin of the radical behaviourist or radical materialist. Just as some may deny the conscious, I’m not about to deny the existence of something deeper in the mind when the epistemological going gets tough. Yet I am neither about to convert it into some great gnostic puzzle, develop a mendacious metapsychology of the unconscious and in so doing raise myself to the station of the great seer into souls. People are complex and very often more than meet the eye. People have faith in their faithlessness and faithlessness in their faith. They both want and don’t want. Something they often don’t want is to know what they don’t want to know (or to know they don’t know what they don’t, or can’t, know). We lie to ourselves. We are always and often in some degree of tension between acknowledging our sins and wanting after a place in ourselves where we may be more comfortable, even if that comfort is self-punishment. We might see in others what we deny in ourselves (projection). Others may remind us of those of the past, leaving us behaving in a way “as if” the person from the past were there in front of us (transference). We may like others to feel what we feel and in so doing solve our problems for us (projective identification). We may have our own neuroses and enter into the career of psychology or psychiatry such that our profession may vicariously heal us (also projective identification, just don’t tell the patient we are more screwed up in psychological knots than they are). We may have difficulty seeing others as persons also of mixed motives and mixed virtues and sins, tending instead to black/white judgments (splitting). There is nothing revelatory about these and other psychotherapeutic terms of art. Great psychoanalysts have always been with us, and draw their power as analysts from our ability to identify with the lesson they are teaching, for some part of us knew the lesson all along. In Sophocles Oedipus, both the protagonist and Jocasta his mother/wife/queen from early in the plot both know yet do not want to know. Deep into his own “psychotherapy” and in his letter to the Roman Church St Paul writes “For I do not do the good I want to do, but the evil I do not want to do, this I keep on doing”. Christ spoke of projection and so did Shakespeare in King Lear, both within the context of puffing up one’s moral vanity via punishing a prostitute. The list of great analysts proceeds down history into Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Nietzsche and Orwell. This is nothing new. The best of them were gone by the 50’s.

The unconscious itself is a metaphor without location or a clear extension. Is it to be seen as existing within the individual alone? If so where is it, and brain scans are, a priori NOT going to provide a sufficient phenomenological and philosophical answer. Actually, they are entirely unhelpful to the question as mind has never been observed in any brain scan, let alone sub mind.

Or is it in the driving force behind collective activities and habits of the group, as was exploited by Freuds nephew Edward Bernays, the propagandist who ought to have joined the pantheon of twentieth century super villains. Is it within or at least connected to some spiritual realm from which comes symbolic representations in the proverbial angel and devil on my shoulder? Can the reader be sure that there is nothing but superstition behind these symbols? Or is the unconscious a post hoc pragmatic explanation for what we do and feel consciously, without the unconscious “being” anything or anywhere at all? Or is the unconscious a disavowed conscious wish, held once fleetingly at the edge of thought before being ignored, as elsewhere suggested. Sometimes the unconscious might not necessarily be some churning magma pushing up from below as much as something someone does not wish to be responsible for being pushed down from above. And what is “down” and “deep” and “up” and “down” anyway when applied to such a construct, except as geometrical metaphor? I’m herein guilty of such non-sense use of spatial language myself, for lack of a better way to describe it.

So much for the form and location of the unconscious. But what of the content? The list of hypothetical dramas deep in the unconscious is as endless as the dramas of the surface self. Indeed, it’s deeper still as we have what the conscious thinks and feels, what the unconscious thinks and feels, and insomuch as each may be symbolic representations of the other there is a third conceptual space wherein lay the interpretation given by the other. In what quasi platonic space can the symbol and the therapy be found?

It is to be made clear to the reader, and this being the confession of one who has invested in being a therapist, that I cannot lay claim to stating as a matter of fact that the unconscious exists at all, much less its form and content, its location, extension and dynamics. I know what I do not know. I know what I cannot know. Yet ISTDP practitioners in their naïve hubris do not know what they do not know. And that is that they also know nothing. Nothing!

Which brings us to the question of how and why traditional psychodynamic psychotherapy and its intensive psychopathic child have acquired the language of the unconscious as being there, psycho-subterranean, to be raised, to be unlocked etcetera etcetera etcetera. Why are they even interested in raising or unlocking anything? Why not just pour tonnes of psychological cement on the nuclear reactor and move on with life? To even countenance such an idea is to be met with accusations of that second greatest of psychiatric sins, i.e. to stigmatize or worse to judge! They will accuse you thus “do you expect them to just move on?”. Well yes in fact. Much of the time that is precisely what I suggest. To love, work and to play is both the evidence of recovery and how it is to be achieved, if it ever will be achieved.

To answer the question of why this drive to raise the unconscious (and construct it as a thing to be raised) I would of course be speculating and guilty of even more imaginative elaborations than that of ISDTP. But oh well. When in Rome….

Firstly, catharsis and “letting it out” are natural to every human with powerful emotions. There’s nothing sophisticated and scientific in such imminent intuitions. So what? More fool psychiatry to have discovered the obvious.

Then there are doctors as doctors, of which Freud was, so is Davanloo and so am I, at least in the sense of our original academic training before beginning on the journey of forgetting real medicine. Incising abscesses and draining out the pus is incredibly satisfying to both patient and physician, and only in the most recent decades has medicine been about putting stuff into the body as opposed to taking stuff out. Take as a further example the case of George Washington, likely killed by his army of presidential physicians letting out the supposed bad blood and exsanguinating him in the process. I cannot help but to wonder if it is the sirens call of unreleased pus that transforms and bewitches the psychiatrist into wanting to play real doctor and take to the patient with a metaphorical scalpel, letting out the pain.

But for the psychiatrist to achieve the zenith of narcissism and identify with the full historical suite of authority figures, they need not simply be doctor, surgeon, magistrate and self-proclaimed philosopher kings. They also need become priests and exorcists. This was outlined in a previous chapter and expanded here.

For the reader unfamiliar with a good exorcism or the film genre, these are the following steps in the drama. Initially the demon possessed host presents either calm or not, yet always with a soul pregnant with the demon within. The priest will begin the ritual (central dynamic sequence of unlocking the unconscious), with a frame or stance towards the spiritual patient and invocations to combat the prince of lies with the king of truth, much as Hickey or Abbass or Davanloo himself makes appeals to “truth”. All this is to say that the exorcism will be supposedly a confrontation with the reality of being, all the lights will come on and all that is hidden and unclean is to be brought to the surface and cast away. During the exorcism there are explorations, made through prayers and questionings, the goal being to know the name of the demon, the discovery if you will of the core traumatized little creature that was cast out of heaven and now just sits stewing and plotting in in primitive murderous rage. Does this sound familiar? Naturally such a creature will make moves towards remaining hidden and misidentified. It will conscript the surface consciousness of the host to “resist”. Minus Hollywood’s dramatic license of spinning heads and superhuman strength of any exorcism film worth its salt, “resistance” and the “unlocking” is much the same in ISTDP. There will be sighs, great muscle tensions and writhing and churnings of the body and its viscera. This is “somatised resistance” and “striated muscle tension”. There may be judgments and projections towards the priest “complex transference feelings”. All the while our intrepid priest moves forward applying “pressure” to know the demons name and have it cast out. And out it will come, perhaps through sigh and shortly after a clenched and tight throat (often a behavioural motif in ISTDP) to our demon shrieking itself out into the night and off into the nearest herd of gentile pigs. Or in the case of ISTDP out comes the primitive murderous rage as discharged affect and good ole fantasy ultraviolence. Either way the demon or “demon” manifests.

The Moral Price of ISTDP

When I first heard about ISTDP it was from enthusiastic colleagues who had attended (expensive) workshops from the travelling apostles of Davanloo. In their eyes danced a sparkle of having discovered something new and exciting, not the usual dying embers of one who long entered the space of therapeutic nihilism and attempting preserve their narcissism by convincing themselves their usual therapy “works”. The faithlessness in their usual therapies (i.e. standard long term dynamic psychotherapy, CBT and DBT to name but a few) was betrayed by this undeniable sparkle of their new love. Still, when they first spoke about the fantasy killing my first impression was that they were surely joking, if only because they seemed not to be in the slightest bit conflicted by what they had seen and what they intended to do with patients themselves. Or I thought perhaps it was an artefact of the workshop example being a patient with an unusually depraved character. And so I obtained the few review papers of the time, titles as mentioned above and several more besides. Lo and behold each mentioned the rage and each mentioned the killing and mutilation. And then I obtained a couple of the lead ISTDP texts, opening pages in random bibliomancy, hoping to see that such cases are an anomaly. Once again in each chosen case transcript was the description of a brutal crime scene, primitive murderous rage. It was as they said.

And so I once again embarked on an informal survey of psychiatric colleague’s attitudes to the therapy. The response almost universally took one of two directions. They either slumbered in amoral pragmatic oblivion, simply not caring or thinking about the moral question “as long as the patient gets better” they would say or “I too have fantasized about killing someone” several others would say as if their normality were moral normativity. Or they found the idea of such a therapy distasteful, though I hazard to add this was only after I made the error of asking the question with my own judgment written on my face. Probably all but one or two likeminded individuals feigned distaste for my benefit. Yet rather than take a stand against it and hold their colleague’s feet to the moral fire, save for one single colleague even those who disliked it turned the blind eye. Psychiatrists only attack psychiatrists who attempt to bring the profession into disrepute, and psychiatric training is a process of deeply entering into the most severe post pragmatic ethical relativism. Most horrifying of all was the fervour with which the true believers embraced it with each successive workshop and sailed beyond the horizon where I could reach their moral sensibilities. This was something approaching the cult mentality I had not seen in twenty years and would not see until covid, proving the obvious that premillennial apocalyptic zealots, age of Aquarian hippies, ideologues of all stripes and supposedly erudite critically thinking “scientific” psychiatrists all share similar DNA, and identical vulnerability to cultism.

I only recall this story to alert the reader who may, like I, reflexively and without apology adjudicate that ISTDP is evil. We cannot assume to be in the majority and have our work cut out for ourselves.

Like any moral argument it can only be made quasi-deductively after an invitation to empathy has been accepted, or the argument will be unconvincing. I will try anyway to make their case for them.

The informal premises are as follows

Premise 1; “if recovery is achieved, all is permissible or even morally good, providing no one is physically hurt”

Premise 2; recovery or mental health is when the patient reports “feeling better”, this report being sufficient without other criteria being applied (esp. moral).

Let us apply it to a few particular cases. Do these premises hold fast to your moral intuitions?

Case 1; imagine you are the grandmother of the patient in Hickey’s published case vignettes, for she is the latest victim of fantasy killing. She is described as being quite feisty, authoritative and stubborn, a “queen bee”. She was a widow from an age before its due. Likely as a European lived during a time of war or had a life coloured by it. There is no description of this grandmother being in an any way a genuine abuser of children, the patient included. Now imagine yourself as the grandmother, and somewhere sometime your granddaughter does this to your reputation and your memory. The reader can if they wish obtain the original papers to find the grandmother arraigned in this fantasy court without the basics of jurisprudential decency and due process. Did the events and relations of the past occur as alleged to have occurred? Upon what pivots the scales to weigh the burden of proof? Is there a dialectic whereby the grandmother is offered any robust defence at all, even a defence of mitigating account for who she was and what she did or did not do? Is the punishment consonant to the crime?

Case 2: Imagine you are one half of a married couple and all that this is meant to entail. Like any human you have your personal insecurities and like any couple you have your shared conflict. The ISTDP patient would assent to the belief that at least some of the conflict is informed by transferences from the past, even unconscious thoughts and feelings about your spouse in the present, and vice versa. So there you are in the kitchen one night, your other half returns home and you enquire as to how that psychotherapy session went. They respond that they feel much better now thank you, a bit guilty yet better nonetheless. They are ready to move forward into the spirit of love that the therapy has opened them up to. So far so good. Not so fast. “what occurred during this therapy” you ask? “Well”, they say, “the climax was truly cathartic. I discovered an intensity of emotion heretofore not experienced”. Your curiosity is piqued and ask to hear more. They continue; ”the climax was a kind of pseudo-dissociation. I was angry, muscles tense and the therapist asked if I wanted to proceed and let it out. I started imagining like it was really happening stabbing someone repeatedly, tearing at the open wounds. I even stabbed at and up their genitalia. At first I thought it was directed at the therapist but the eye colour didn’t match”. Then who were you killing and mutilating you ask? “it was you dearest” comes their reply, “It was you”.

Case 3; case number 3 is identical to the first, except the mutilated, defiled and tossed around object of a self-centered catharsis is a child. After all, as any parent knows children can be the catalyst of much angst. So they too ought be liable to some ole fantasy ultraviolence? Remember what the morality of ISTDP demands, or why would the therapist partake in it i.e., what is not done to the flesh is morally neutral at the least. Now do not flinch. Imagine this scenario of fantasizing in a substantial way (with role play) torturing and killing a child. Get out your claws and knives. Do your worst. Release also the sexualized content of the rage. No one is really hurt. Is this a price worth paying to “feel better”?

So I ask the reader what their moral impressions to these cases are, not as a crime of thought the like of which ought to be instantiated into the criminal code by the legislature, for such an inclusion of thought crime would be another kind of evil, and contra the conditionally libertarian thrust of this book you are kind enough to read. No, I’m asking the reader to be the judge in the court of their own heart, of the mind and of the family. If you were the physically unscathed spouse or co-parent of the child what would this disclosure do to the relationship. What would it say about it? And what if you did not even ask that evening in the kitchen. What does it mean that the fantasy killing happened? What does it mean that psychiatry simply does not care about these questions?

But ISTDP works?

Does it? I’m not convinced on its own terms or that of so called “evidence based medicine”, and my own philosophical commitment is that it is absurd to attempt quantify and measure the human condition and purpose of life. For those persons who attempt to couple the idea of psychodynamic with psychometric I can have only pity. In any case the evidence of effect is a distraction and the value free appeal to evidence is itself a sign of utter moral famine. But let us grant it actually worked, in the sense that the patient comes in with anxiety or emotional instability or OCD or somatised pain or whatever blah blah blah and walks out utterly cured of these symptoms, along with all the attendant dysfunction in their social and occupational now restored. Now the question becomes a more nuanced one, one where I cannot avoid returning to the priest and the metaphor of exorcism once more. Faithful or faithless the reader may be. It does not matter. The moral sensibilities are the same. Here we approach the question of just what therapy of the psyche is. Should therapy be a confrontation with one’s character and cultivation of the better virtues? Or should it be the atomized consumerist want to feel happy and void of unpleasant thoughts and feelings? Are we to take a leaf from the book of Seneca or of Crowley, the latter of whom would say “Do what thou wilt. That is the whole of the law”. Here we approach the question of what would it profit a man (or woman) if s/he inherits the world and loses their own soul. So you feel better. That’s nice. You sleep better at night. That’s good too. You cross the street without trepidation and jump into the pool of life without casting the toe in first. Bravo. But has the demon been cast out? No, for the demon is you if you are the patient, not now in a herd of pigs heading for the cliff, and not in the fantasized corpse of your parent or grandparent. The demon, if you will continue indulge me the metaphor, is now an alleged unconscious sated of its desire for murderous discharge, that is until another supposed loved one irks it. It remains within you after the initial miracle of ISTDP sessions and those “top up” sessions usually deemed necessary down the track (so much for an advance on analysis interminable). Insomuch as the unconscious is the stuff of speculation and the conscious is the stuff of undeniable interior reality, the question is who consciously chose the therapy? You. And who consciously assented to the pseudo-exorcism and being a killer who ought to have his kill? You. That is to say who consciously constructed themselves as a choice to be what ISTDP says you are, without a shred of evidence? You. Who is making a living statement about what other humans are as depraved killers varnished with a thin coat of conscious neurosis? You. Who fantasy killed someone without any access to fantasy due process for the victim? You. And who propagates this ontology of the person. If you are the therapist? This too is you.

You see the religious metaphor rings louder still. I’m reminded of a warning from an exorcist (or psychotherapist?) of old. Here is the advice. When the demon is cast out we must be cautious it does not roam about and soon return to the newly cleaned house with a legion of friends, all more cunning, covert and evil than the next. ISTDP is both the pseudo-exorcism and this stronger repossession with a damaged character even more deserving of condemnation, all rolled up in one seamless package. The prince of lies indeed, Satan (if you’ll pardon me the metaphor) just exorcised the human out of the demon and convinced a demon its human.

A Return to Genealogy of ISTDP

What is curiously lacking in all of the gospels of Davanloo, as far as I can tell, is what Davanloo himself was exposed to in the days before video. You see Davanloo was a trainee of Erich Lindemann, who in turn was no ordinary analyst. Erich Lindemann was the attending psychiatrist following the Cocoanut Grove Nightclub fire the evening of November 28th 1942. Cocoanut Grove was the closest the mainland United States came to the flames of war that raged across Europe at the time, a terrible taste of transatlantic daily life, and just about the only thing that knocked the war off the front page of the newspapers. That November evening the club was packed beyond capacity with almost one thousand souls, flammable faux palms and even more flammable drapery from floor to ceiling and across the top. Some of this drapery even concealed potential exits. With hopelessly inadequate observable exits to cater for literally hundreds of terrified patrons clamoring in flames and smoky darkness for a way out, by the end of the night almost five hundred were scorched or dead from carbon monoxide poisoning. Scores of others were horribly burned and scarred for life. This is trauma with an upper case “T” before the construct of PTSD was developed as it is now, and long before Kubler Ross developed her stages of grief. And what did Lindemann discover? Lindemann discovered deformed and injured club patrons and surviving loved ones in extremis of grief and emotional discharge. Often this was delayed days or weeks after the event. Yes, there were clenched muscles and throats held tight against the release of screams that would come in their due time and season. And yes Lindemann encountered much survivor rage also, with the club. Rage against fate, with God, with oneself, with club management, with the ignoble irony of being a wartime casualty of peacetime frivolity, and even anger with the loved ones themselves for being there that night of all nights and not some other time. The similarities between the somatic reactions and abreactions bear almost identical similarity to Davanloos ISTDP as if the latter were a dissimulated trading on the echo of the screams from Cocoanut Grove down to this day. I can’t help but wonder if ISTDP is not Davanloos way of saying that if there is no fire to be found, one might as well pretend there was one anyway and light it from the sparks of the patient’s imagination. The crucial point for one with moral sensibilities is that anyone of common decency can empathize with the loved one left behind after the Cocoanut Grove, along with their moment or moments of rage after such a tragedy. Were any to leap on the grave with fists thumping who could say this was anyone other than a suffering human. However much the behaviour might be inappropriate it would at least be empathically meaningful and evoke pity. There but by the grace of God or the luck of the void go I, that their grief is not mine. It is this same empathic hook that drives the fans of the vigilante film genre. We can tolerate gratuitous excesses of cinematic violence to be inflicted on a depraved criminal who deserves it from a victim who alone carries the burden of vengeance upon them. But stabbing little old grannies, even little bad grannies, to feel better. This simply won’t do.

A Return to Training; An Eye on the Eye Makes the Whole World Blind

Psychotherapy training has long valued the place of role play and observation of therapy sessions. One can hardly fault the reasoning behind this. Seeing and doing are axiomatic to any form of training. Neither can one fault the inclusion of technologies such as videorecording and access of archival material to the same end of teaching the novice. And neither can a critic so quickly draw a negative conclusion from a therapy that would ask the trainee receive therapy themselves, though universalizing this may be a praxis ad absurdum (or medical students would graduate with many surgical scars, no uterus or appendix and having had every orifice explored). Indeed except for Freud himself (who self-analyzed), all apostles and disciples of apostles of psychanalysis were expected to take to the couch, this being an anointing into themselves becoming analysts.

However, all of these conventions of training serve to provide cover for what may be another sinister side to ISTDP’s immorality and to cloud the therapist from insight into their own trespass against decency. As was clearly stated in Hickeys papers, trainee therapists themselves are filmed not simply in role playing patients, but as being bone fide patients. Imagine if you will that the therapist might at some point hear the whisper of that small voice of conscience suggesting the moral arguments I have made. You see it is easy for me to heed the moral voice as I have never allowed myself fall sway to the cult of Davanloo. I have not, in the way of Davanloo, found fantasy blood on my hands. But what if I had been in the chair itself, stabbing and slashing away at my own dearly departed grannies while that little light on the video camera glowed “recording” whilst a nest of voyeur trainees looking on? What if I had facilitated others in committing the same fantasy ultraviolence, again, and again and again? And what if in the camera I had the symbolic presence of the all seeing eye of Davanloo in each of my sessions as therapist, no matter where I roam around the world? Would I not then be disinclined to wish to see my own moral crimes? This reminds me of that grainy online video of the Ba’ath Party conference when Saddam Hussein gave one half of his ministers pistols and instructed them to shoot the other half of their comrades. Just how can you extricate yourself from a monster after such an immoral buy in, when you have become the monster yourself? The execution as group initiation is as old as man.

What’s the alternative?

Once at a presentation I was asked what the alternative to psychodynamic psychiatry in general and ISTDP in particular might be, as if to imply there must be something and I am obliged to have it ready on a plate. That’s also a question asked when I might be on the verge of convincing another that SSRI’s should usually be thrown into the trash. “What will you give me instead to make me happy?”

But why do they ask this? Isn’t enough to negate what ought to be negated? The ready and welcome answer against psychotherapy for many a biologically minded psychiatrist is to recourse to medication. But in the proverbial nine times out of ten, psychotropic medication has non-specific salutatory effects, adverse effects that the psychiatrist assiduously downplays the significance of, and medication fails utterly to engage with the patient’s personality and challenges within their life. It is, to borrow that overused metaphor, a “bandaid solution”. Regarding psychotropic medication, these are heavy statements made without evidence, yet others have argued the same more comprehensively than I and the reader can explore elsewhere if they wish not to take my word for it. Moreover, as any reader of Huxley’s Brave New World is aware, psychotropic medication can dull the mind against the pains which might be the drivers towards necessary change in the patient’s own life, in addition to that of the world around them. We return to the assumption that feeling better is being better.

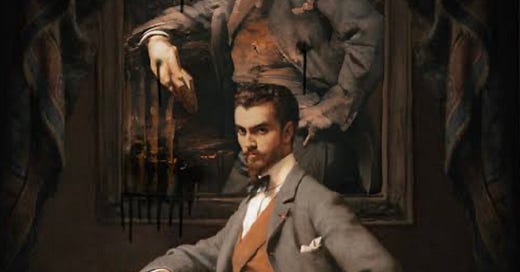

We likewise cycle back to the question of psychotherapy. Even here the question is not one in which psychiatry ought to assume it’s need to live on in some form or another. Freud himself paved the way to analysts without medical degrees (arguably to give his daughter and heir a royal road to his throne). In answering the question asked of me “what do we do without traditional psychotherapy” I’m impressed with the subtext. The want is not, I suspect, for the patients good, as opposed to the want to keep a profession going for the profession’s sake. And so it will only let go of one rung of the ladder if it has another to grasp hold of. Here we approach what psychiatry as a profession has in common with ISTDP patients, i.e. the willingness to kill off the other providing it (psychiatry) walks away unscathed. But why is the blade never turned towards the self? The dearth of fantasy self-killing in ISTDP is extremely telling. That and the whole superstructure of psychiatric guild and practice speaks of a covert (and often overt) narcissism held even when some unconvincing humility and guilt is placed on display. Psychiatry has always been able attacked its past only to suppose that it is forever moving into a glorious future through an adequate present. In the final chapter I’ll propose what such an alternative psychotherapy might be, this essentially being no therapy at all. Suffice to say for now that whether we be patient or psychotherapist, we ought not to be architects of our own Dorian Grays, where the superficial psyche is restored to the appearances of beauty and functionality at the expense of corrupting our true selves. Gray kept his portrait as a yardstick to his own depravity and need for redemption. ISTDP keeps theirs’s on video.

Fascinating. I'm gonna hunt down some material on ISTDP and see whether it's another tool to consider for our biopolitical pharmaganda warfare

Hey this looks excellent and is very thorough from the quick skim I read. Bit tired currently but i've been looking for insights & hypotheses from the psych community in particular recently. Will bookmark for later and reply comment in detail.

Last few days were full of researching Perceptual Control Theory, knowledge systems, PsyWar and other related interdiscliplinary fields under the umbrella of Vaccination Social Sciences. I love it, but it's taxing, moreso than reading scientific biochem papers or studies.